Anatomy of the chronic hryvna devaluation

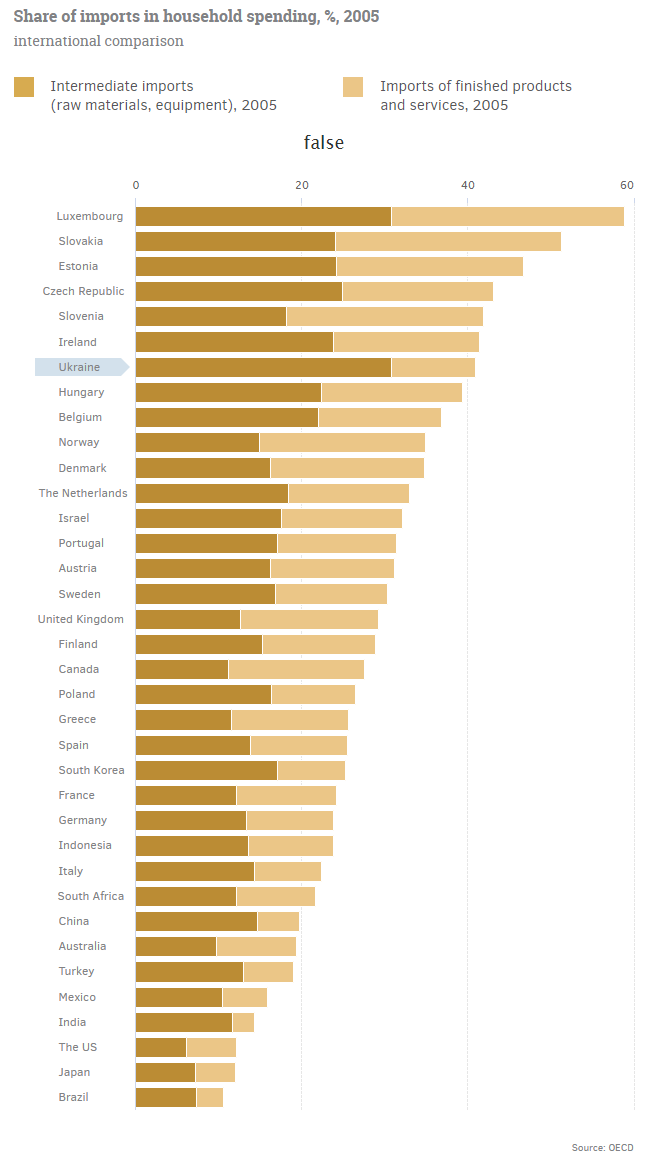

1. In the years since the country became independent, Ukraine has become part of the global economy: the penetration of imports in its consumption is one of the highest in the world.

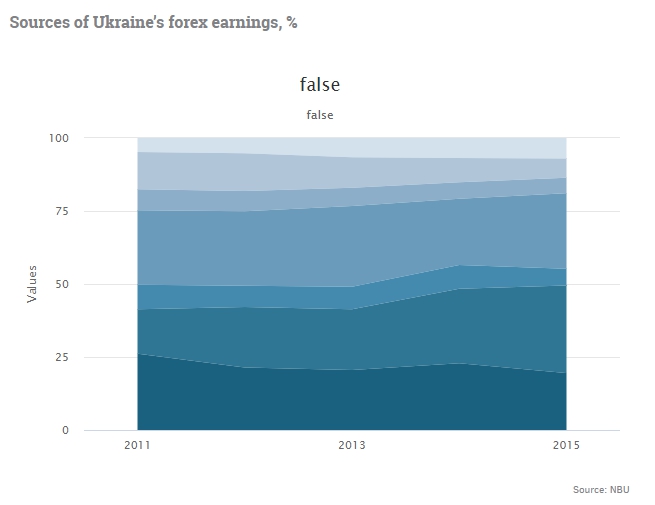

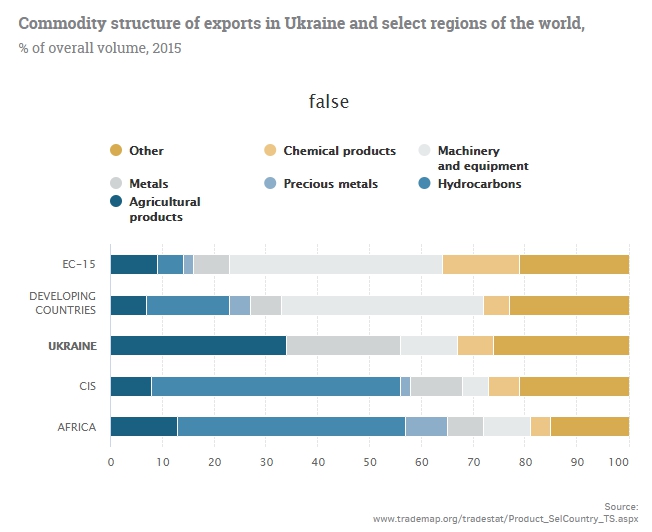

2. Although Ukraine has learned to consume quality goods, it hasn’t yet learned to make quality goods: its main forex earnings come from exporting metals and agricultural products.

3. More competitive countries earn their forex from selling goods and services, such as high-tech exports, that are largely unaffected by fluctuations on commodities markets. This guarantees the stability of forex income, regardless of resource shocks. Meanwhile, developing countries export fuels and primary raw materials with low added value, making them very vulnerable to periodic declines in resource prices.

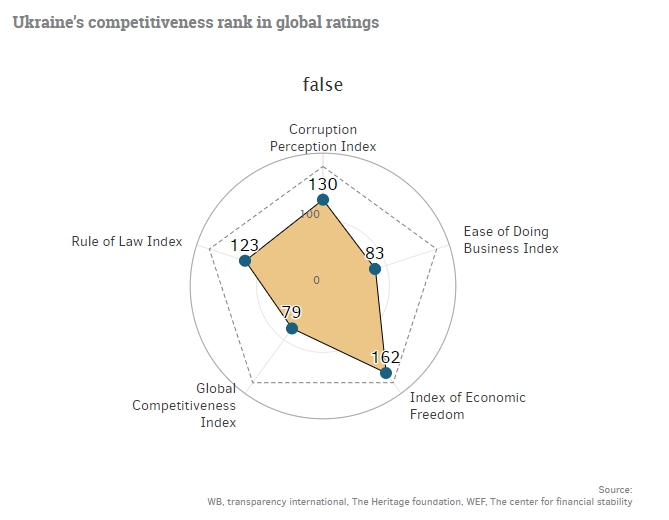

4. An unfavorable business climate is the main reason why Ukrainian businesses are only interested in selling, and not in manufacturing anything.

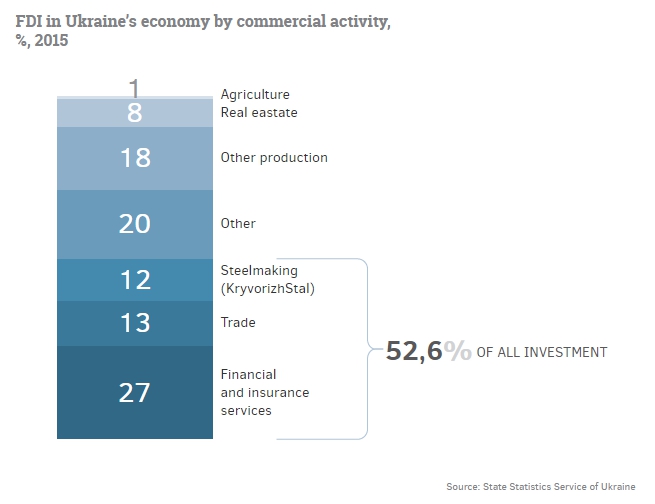

5. Even the inflow of foreign investment isn’t helping Ukraine much because most foreign investors have so far been investing in (a) the banking sector, that is, fueling lending to purchase imports; (b) the trade sector, because it’s more convenient to sell than to manufacture in Ukraine; and (c) the privatization of KryvorizhStal. Altogether, these three sources of investment account for more than 50% of all FDI inflows to Ukraine.

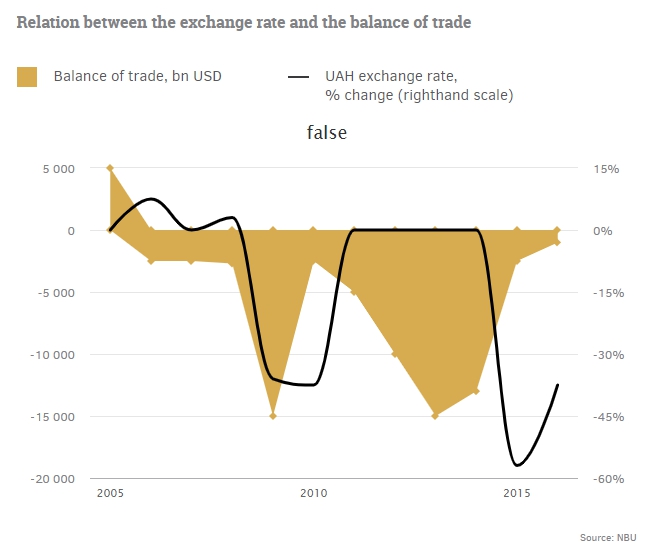

6. As a consequence, Ukraine’s trade balance only improves after a monetary shock, when the devaluation of the hryvnia “kills” imports. As soon as the economy picks up again, imports immediately start to outpace exports.

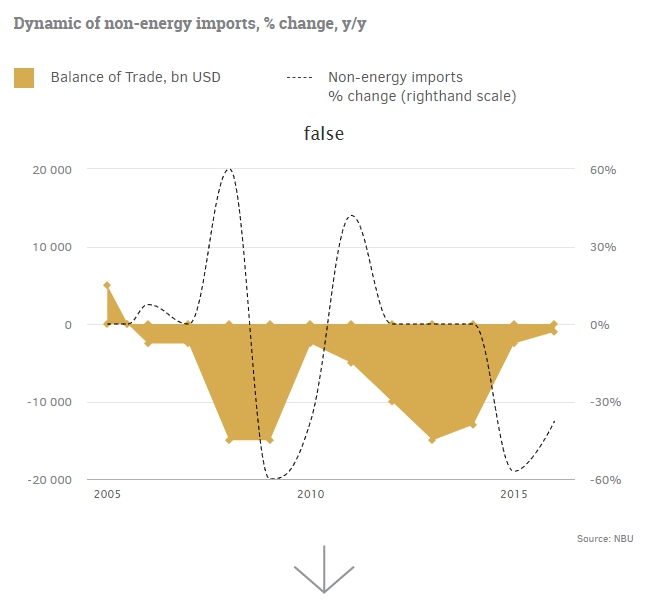

7. Today, the situation has not changed and Ukraine can already see portents of growing pressure on the hryvnia: non-energy imports are sharply on the rise.

And so, until Ukraine does something about its investment appeal and the appearance of new production facilities stops being the exception rather than the rule, chronic devaluation will continue to plague the country for a long time to come.